Science

Angular Velocity

Rowden Fullen (1990’s)

Look at the skater spinning on the point of one skate. The original momentum continues to spin him, if he holds his arms outstretched, until friction gradually slows him down. However if the arms are drawn in and folded across the chest the speed of rotation (angular velocity) is markedly increased.

What concerns us here is the centre of gravity of the arm in relation to the speed of rotation. At the original angular velocity the centre of gravity of the arm will traverse a certain circular distance in a given time period. However when the arm’s centre of gravity is drawn in towards the centre of rotation, it follows a circular path of smaller radius and shorter circumference. Therefore if the body were to rotate at the same angular velocity, the distance traversed by the arm’s centre of gravity would be much smaller in the given time period — which is not possible under the law of conservation of angular momentum.

Discounting the outside forces such as air resistance and friction between the base and the surface of the ice, angular momentum must remain constant. When one component such as the distance from the centre of gravity of the arm to the centre of rotation of the body is decreased, then there must be a corresponding increase in another component, the angular velocity and vice versa. Therefore when the arm’s centre of gravity is drawn in, the angular velocity is increased sufficiently so that the arm’s new centre of gravity traverses in the same given time period, a distance equal to that which it would have done along the wider original circle.

Coaches can easily work out for themselves the advantages in the rotational value of the short-arm loops and the desirability of working on these in preference to the long-arm strokes, unless the physique of their player is particularly suited to this latter area. The principle is of especial interest when working in the girls’ and women’s game where our subjects have much less body strength and need to use this as effectively as possible. Obviously a faster and shorter arm movement with good rotation will put much less stress on the back area while producing a very effective stroke.

The Axis

Rowden Fullen (1990’s)

A table tennis ball has no fixed axis in itself. But once it spins, an axis will naturally come into being.

A table tennis ball can produce three kinds of basic axes, topspin, backspin or sidespin to left or right. Rarely however do you get pure spin on just one axis, almost always there is a combination of spins, topspin and sidespin, sidespin and backspin. Quite often one spin will predominate but there will be more than one present. This is because very few of us play ‘pure’ strokes, we loop for example but not just with topspin, our stroke incorporates an element of sidespin, sometimes more sometimes less. Occasionally we get ‘float’ balls almost completely without spin, where you can clearly see the ‘trademark’ on the ball in flight, (if you watch the ball at the right time, not after the bounce when the ball will ‘acquire’ topspin).

The fact that the ball has an axis also means that there are two places on the ball, the two ‘poles’, where there is no spin even on the most viciously spinning ball. This is particularly useful information, because if you are able to make use of the ‘poles’ in your stroke play, you can in fact bypass the spin. If you can play a short sidespin serve at the pole underneath, then you can return all the server’s spin. Or if for example you have just killed a ball wide out to the opponent’s backhand and he chops it back to the middle with extreme backspin, you can bypass the spin by driving the ball with your forehand to the opponent’s forehand corner. By playing to the forehand you hit the ball near to the pole, if you played back to the backhand you would strike the ball on the ‘equator’ or the area of most spin.

The variation in axes is what causes the biggest problem when playing against long pimple or anti-loop rubbers. You serve for example with immense sidespin and backspin — the opponent pushes the ball back but because his or her racket doesn’t affect the spin on the ball, you get a topspin return with a sidespin kick and you wonder what has happened! In fact you just got your own spin back. You get topspin back because your backspin remains on the ball (if the opponent returns the ball, without changing the spin, then it must come back with topspin because the ball continues to spin in the same direction) and you get the same sidespin back as you initiated.

Elastic Energy in Stroke Play

Rowden Fullen (1990’s)

Many sporting activities involve a stretch-shorten cycle where the muscles involved in the exercise are first stretched then shortened. This is generally observed in racket sports as a counter-movement during the back-swing or preparation stage of the activity (the stretching phase), that precedes the actual forward or upward movement (the shortening phase). One of the reasons for the use of the stretch-shorten cycle is that it enhances the quality and efficiency of the movement through the utilization of elastic energy.

The mechanical principle underlying the use of elastic energy in stretch-shorten cycle activities is a relatively simple process. During the stretching phase the muscles and tendons are actually stretched and store elastic energy in the same way as an elastic band stores energy when stretched. On movement reversal, during the shortening phase, the stretched muscles and tendons recoil back to their original shape and in so doing a portion of the stored energy is recovered and assists in the movement.

Biomechanical research has shown that, in running for example, the use of elastic energy has been estimated to account for approximately 50% of the total energy requirement. In other similar stretch-shorten cycle activities such as racket sports, (movement and stroke play for example), the use of elastic energy also contributes a significant proportion to the total energy requirement.

Elastic energy is stored in tendons and in muscle itself. The storage of elastic energy within muscle is dependent upon the level of muscular activity present during the stretching phase. The greater the tension in the muscle being stretched, the more elastic energy will be stored. Therefore, to maximize the storage of elastic energy, the stretching phase should be resisted by muscular effort. In a stretching movement of very short duration, such as the foot contact phase in sprinting, the energy can be stored during the entire stretching motion. However, in a movement of longer duration, such as in a forehand topspin, the energy is best stored just prior to the shortening phase. This is achieved by producing a high level of force, (large muscular resistance), towards the end of the stretching phase.

Research indicates also that increasing the speed of the stretching phase from a slow speed to a relatively high speed enhances the storage of elastic energy. This occurs as an increased speed or force of stretch extends the muscles and tendons to a greater extent thus storing even more energy. Therefore the final portion of the back-swing should be performed quickly as the faster the back-swing, the greater the elastic energy recoil will be during the forward swing. In the case of our attacking (or defensive) strokes in table tennis it is important that these stretch-shorten cycle movements be performed with a minimal delay between the stretch and shorten phases.

It has been demonstrated that 93% of stored elastic energy can be recovered. This recovery is largely dependent on the time period between the stretching and shortening movement phases. Elastic energy is reduced if a delay period occurs during the stretch-shorten cycle because during the delay period the stored energy is released as heat. The longer the delay the greater the loss of elastic energy. Research indicates that after a delay period of around one second, 55% of the stored energy is lost — after 2 seconds, 80% and after 4 seconds there is total loss.

Some training practices encourage players to prepare very early for stroke production and this often inadvertently produces a delay period between the back-swing and forward swing of the stroke. As a result stored energy is lost and an inefficient movement strategy results. For maximum efficiency players must practise allowing the back-swing and forward swing to flow naturally from one phase of the movement to the other. This is particularly important when playing defensive players, where there can be some seconds’ time-lag in returning the ball. Try more to move into a good position, but only to pull back the arm in the stretch phase of the topspin or drive movement at the time the ball bounces on your side of the table or even after. In this way you save a higher ratio of elastic energy and utilize it in the stroke.

The recovery of stored elastic energy tends to occur relatively quickly during the shortening phase of the movement. Tests show that all stored energy is released 0.25 seconds into the shortening phase. Thus in drive and topspin strokes the stored energy is used primarily to assist in the early forward swing stage of the movement.

The implications from this research are that the stretching or counter-movement phase should be performed quickly with large muscular resistance exerted over the final 0.2 seconds and that all stretch-shorten cycle movements should be performed with a minimal delay between the stretch and shorten phases.

Other research indicates that plyometric training (depth jumping, bounding etc.) may also enhance an athlete’s ability to utilize elastic energy and may even alter the elasticity of the tendons and muscles enabling them to store greater quantities of energy. Also in such training, the delay time between the stretch-shorten cycle is minimized ensuring maximal recovery of all stored energy. It would appear that plyometric training, as compared to conventional weight training, involves the implementation of those movement strategies which maximize the contribution of elastic energy to stretch-shorten cycle movements.

However although plyometric exercises may represent a more specific form of overload for many athletes, the performance of high impact stretching movements often results in muscle soreness in the days following training. It may therefore be necessary that the implementation of plyometrics in a training routine allows for recovery days between exercise sessions.

The Main Theme

Rowden Fullen (2003)

We have to remember that table tennis is above all an individual contest against another individual. Far too often in our modern society we are prone to stress the group aspects of sport and the individual emphasis is lost. Not only is table tennis an individual sport but it places heavy demands on participants and to cope they need to be well developed in a number of differing areas.

The main theme running through all coaching development must be the individual focus – yet to a large extent in Europe we now give far more attention to the group needs. The more individual approach naturally places altered demands on the trainers and coaches and also changes the working methods. For example no coach however expert can be a specialist in all the diverse spheres of table tennis. Even within the technical areas we have specialist fields such as style development, serve and receive, women’s or doubles play, use of materials, multi-ball, defenders and penholders for example. In addition to what we may regard purely as table tennis, we have aspects such as the physical and psychological sides plus areas such as diet, massage and sports injuries.

At the highest level where we have just one or two coaches deciding the coaching policy and direction or writing coaching manuals for any one country, to perform adequately they will have to refer to outside experts where they themselves lack knowledge. In a number of countries in Europe the coaching manuals include and pay tribute to articles by up to a dozen or more ‘specialists’.

The same applies also to developing players – what we need is a coaching team, using a number of coaches with their own specialist skills. This type of approach will almost always lead to more playing styles and will stimulate players to be more creative and inventive. The coaching team will of course bring differing skills, knowledge and experience which will compliment one another. Another factor is to build up access to the supporting aspects, mental training, physical testing, dietary, massage and injury experts. It also goes without saying that the various team members, whether coaches or supporting specialists, respect each other’s expertise and are prepared to work together from the outset. Far too often our sport seems to engender both a parochial and proprietorial attitude towards players – even national coaches are not immune.

The capacity to reach the heights is in more of us than we may think. It takes a long time to be a top player and the road is beset by many pitfalls, but one of the most important qualities of the coach is to believe in his player and to support him or her at all times. For the player it’s vital that he or she works with his or her own goals, which cannot be influenced by others. If we can only create the right environment then many more players will be able to achieve their full potential.

Theory of Spin

Rowden Fullen(2000)

- In 1960 Jacobson brought the loop back after training in Japan and became a sensation in England beating all comers.

- The initial loop technique was with a ‘fine’ touch and slow, with a high arc. This type of loop had an unpredictable bounce due to the ‘Magnus’ effect. Often the ball dropped low very quickly causing problems for defensive players.

- There was a big difference between the hard rackets of the ‘50’s and the modern sandwich rackets. The new surface was much softer and more ‘tacky’ allowing the ball to sink in and be gripped. As a result the contact angle used to strike the ball changed dramatically. Players were able to strike the ball with a much more closed racket angle, which resulted in very much increased topspin.

- Using a more closed racket angle not only could players achieve much more spin, but also they had the capability of hitting the ball much harder and still getting it on the table!

- Striking the ball with a closed racket angle with power means SPIN. The harder the player can hit the ball the more SPIN is generated. Women have a lesser capability than men do to hit the ball really hard.

- We are aware that it is necessary to have a ‘thin’ contact in order to achieve good spin. However if the contact is too fine, we will not produce strong spin, however much force we apply. This is of course because the ball is not given enough friction and it will just slide off the bat surface without being held long enough to obtain the required effect.

- Spin affects the ball in flight and after bouncing. This is known as the ‘MAGNUS’ effect and is to do with the high-pressure part of a spinning object impacting against the air pressure. Generally with topspin there is a smaller angle after the bounce and with backspin a larger one.

- Sometimes with the slower loop, high with spin and no speed, we encounter unusual bounces. This is to do with the angle of contact with the table. Because the prime speed is downwards, the ball ‘kicks’ up first, then ‘drops’ low very quickly. The same happens with the fast chop especially if this is taken early against a rising ball. The return ‘comes through’ fast and instead of ‘kicking’ up skids through very low.

The 4 Elements

Rowden Fullen (2003)

| SPEED | PLACEMENT | SPIN | POWER |

To reach the highest levels players must master these four aspects, be able to utilize them in play and have the capability of switching from one to the other. They must have the ability to combine these elements in their game when competing. If players are weak in one or more of these areas, they are unlikely to achieve real success in our sport. Often in the case of older established stars it is when one or more of the 4 elements weaken or when they are no longer able to combine them effectively, that their playing level starts to decline.

Of the four elements, power and spin assume more importance in the men’s game and speed and placement more in the women’s. Men use topspin more than women and it is necessary in order to create strong spin on a fast shot to hit the ball hard. The harder you can hit the ball with a closed racket, the more topspin you will produce. Women don’t hit the ball as hard as men do, so they achieve less spin and have less on-the-table control. It is speed and control of speed which is rather more important with women’s play. The ability to loop several balls in a row is not a prime requirement. Instead timing is vital as women drive much more – the timing window in drive play is extremely narrow, between ‘peak’ and 1 – 2 centimetres before.

Length also assumes much more importance with women’s play, as does placement. In the men’s game power with strong topspin means that the ball accelerates after bouncing and leaves the opponent’s side of the table with a much flatter trajectory. The vast majority of men counter from a deeper position and give themselves time. From this deeper position it is of course much more difficult to vary placement. Men more often than not look to place the first opening ball and once the rally deteriorates into control and counter-control back from the table then power and spin are the main elements. In the women’s game almost all players assume a much closer-to-table position and it is rather easier to vary placement, long and short or to the angles and to vary speed. Because women have a closer position it is inevitable too that a bad length ball is easily smashed. It is crucial that women can spin short or long and not mid-table.

As a result women really need to open in a different way to men. The ability for example to open hard against the first backspin ball and not spin all the time is a vital asset. Even the way that women loop, if they open with spin, is critical. This should not be hard and fast as in the men’s game for without the extreme spin that the men are capable of creating, the fast loop executed by women is more predictable and easier to block or to counter, particularly when the opponent is much closer to the table.

Women should be looking rather more to open with a slower ball, with finer touch, good spin and good length. More often than not this will create openings to drive or smash the next ball. Indeed rather than regarding topspin as an end in itself as the men do, women should look upon it as a weapon, a means to create openings from which they can win the point.

As we indicated at the start of this article the ability to combine these 4 elements, power and spin and speed and placement, into your game when competing, will have a direct significance on your ultimate level of play. Against the top players a weakness in any one aspect will be exploited instantly and will be a limiting factor in your own development.

Effective Practice

Rowden Fullen (2004)

The training hall is the arena in which athletes learn and develop techniques and skills. The prime skill of table tennis is the ability to adapt to an ever changing situation and to do this at speed – it is obvious therefore that our sport is an open skill and learning to execute the same technique time and time again is not as important as developing the ability to select the most appropriate technique to suit a changing situation.

Training must provide continuous and evolving possibilities for our athletes to apply a variety of techniques in a realistic and competitive environment. Coaches must ensure that players, as they progress through the learning process, are able to identify the most suitable technique and apply this in a variety of differing situations. Even with an open skill such as ours, it is vital to develop an automatic or subconscious reaction level (as this is how we play best) but because we are facing a rapidly changing situation all the time, to cultivate adaptive intelligence is absolutely vital. How do we do this? In a number of ways – we must for example:

- train against all styles of play, penholders, left-handers, blockers, loop players, defenders, long pimple players etc.

- learn to read the game more quickly (watching opponent’s body action etc.)

- train in right way, using variable/random or thinking situation exercises.

- use alternative training, such as multi-ball and use this technique in a variable/random manner.

The coach should also try to identify a new way forward with players working from their own experience and perceptions rather than his own. In our sport the most effective way for the performer to increase physical efficiency is to become increasingly aware of the physical sensations during activity. The awareness of bodily sensations is crucial to the development of skills. Unfortunately the majority of coaches persist in imposing their technique from outside. No two human minds or bodies are the same – how can the coach tell the player how to use his or hers to best effect, only the player can do this by being aware! Let us try to encourage our players to use their own intrinsic feedback to maintain and to refine their competence in applying various techniques.

Practice and how to do this should be evaluated in terms of short and long-term gains and also in terms of memory retention – some training methods result in rather better long-term retention and performance than others. We also of course need to practise in the right way so that we are able to adapt and quickly in the face of the myriad differing situations we will face in competition.

Constant exercises where we repeat exactly the same stroke to the same place, with the same length and the same spin are usually not very useful in transferring techniques into a competitive environment. Each shot is identical to the next and the previous and the technique is very specific. Such exercises are of more use in closed situations such as shooting rather than in learning open skills such as in our sport, where we continually face new and differing challenges.

Blocked exercises are also very similar where we repeat the same stroke but with minor variations in pace, length, spin etc. Again one technique performed repeatedly hinders the transfer of technique into an open or competitive environment. Such practice may appear very efficient and looks good, but is unlikely to have any lasting learning effect and will usually break down in competition, where we don’t meet the same predictability.

Variable practice is when performers try to deliberately vary the execution of one technique, using differing speeds, spins, heights and placement. This helps performers to learn the technique more effectively, helps its recall and retention into the long-term memory banks and helps with the transfer of the technique into a competitive situation.

Random practice where we mix a variety of techniques, not only helps recall and retention but also develops the ability to select the most appropriate technique for the situation and is most beneficial to an open skill such as table tennis. Obviously this type of practice most replicates the competitive environment and also forces the player to be actively involved in the learning process.

Mental practice of techniques can also help the learning process especially if we imagine executing the technique using all the senses – the resulting image is then that much more vivid and realistic. Use of mental imagery can be particularly helpful when recovering from injury, learning new techniques and when preparing for the big match or tournament.

The main problem in our sport is the instability of the environment. The player must be effective in a constantly evolving situation. High level players for example learn from mistakes immediately and do not repeat errors – they find effective solutions rapidly. Adaptive intelligence is the ability to evaluate a scenario in an instant, take in all the immediately available solutions and then take the best action. Often this is called reactive thinking – the ability to think clearly under pressure and use any available means to hand to resolve the problem. To be a really successful top-level table tennis player requires the nurturing and evolution of this aptitude – for the top coach to produce top players he or she has to be constantly aware of this fact and also be aware of the means of stimulating and fostering this ability. Regrettably too many of the training exercises we continue to use even at quite high level in Europe still reinforce predictability rather than adaptive intelligence.

Above all however it must be understood that for any practice to be effective it must be tailored to the style of the individual player. Players are individuals with a host of differing ways of playing. Exercises which are very beneficial to one player may in fact be detrimental to another. The prime criterion of the value of practice to the individual is whether or not this complements the player’s evolution. For this to happen the player must be aware of the direction of his or her development and the means of achieving maximum potential – unfortunately a number of players go through their whole career without ever understanding this.

5 Steps to Developing Players

Rowden Fullen (2003)

1. Sparring — Why do you train?

You train as preparation for competition therefore sparring is of vital importance. However the strength and intensity of sparring is important and it’s vital too that you have opposition at a variety of levels. Many players seem to think for example that you can only improve by training with much higher level sparring than yourself. If you always play only against much better performers than yourself, how do you ever learn to impose your game on others and to develop your own tactical ploys? The better player is always in control! You need in fact to practise at three levels.

- With players better than yourself to learn new things and to upgrade your skills.

- With players of similar standard to work out new tactics and to try to control the play.

- With players of lesser ability where you can control the game and have more opportunities to use your more powerful strokes.

2. Group interaction

The importance of being in a good group with a variety of playing styles cannot be over-emphasized — this creates the ‘right’ training environment where all the players are ready to work for the others and to contribute to the group development. It is so vital for coaches to ensure that their players, right from the formative years, have the opportunity to train and to play against all styles of play and combinations of material. In this way the ‘automatic’ reflexes, the conditioned responses, that players have to work so hard to build up, cover a much larger series of actions and it is rather easier for them to adapt to new situations as they develop and progress to higher levels. In other words the content and method of training assume rather more importance than we may have initially thought, especially in the formative years. If players are to reach top level and realize their full potential it is vital that they are taught to build up a high adaptive capability in the early years.

3. Individual emphasis

Players who have good potential need individual attention. Several aspects of coaching, consciousness, tactics, the mental side, serve and receive, style development etc. are developed much more readily when tackled on a one to one basis. The coach is also able to feel for himself the strengths and weaknesses of the player and to understand in which areas training should be focussed.

4. Direction

Coaches must appreciate that each player is an individual and different and should be directed towards his or her own individual style of play and towards his or her strengths. And even after we have stressed the importance of basics, we should perhaps emphasize even more that none of us can ever be dogmatic about technique. It is not how the player plays the stroke that is vital but whether he or she observes the underlying principles and whether it is effective! There is absolutely no use in having a stroke that looks nice, is technically perfect, but has no effect.

Bear in mind too the concept of the player having his or her own idiosyncrasies, the idea of individual techniques but within the underlying principles is vital if the player is to cultivate his or her own personal style of play. Six players executing a forehand topspin will do so in six differing ways, with varied pace, varied spin, varied placement, a little element of sidespin etc. None of these is ‘wrong’. What we are looking at here is the concept of individual ‘flair’, but within the underlying principles, the critical features of the stroke.

What the coach should be looking at also is how such unique characteristics can be turned to advantage. Does the player have a ‘specialty’, something a little different which causes problems to opponents — or are there aspects of his or her game which can be accentuated to fashion such a specialty.

Another aspect that many players and coaches do not seem to appreciate is that development must be in the right direction for the particular player and that the right training must be devised to enable that player to evolve and mature. Indeed it is the prime function of the coach to unlock the potential of his player. Direction is vital, if the player follows the wrong course for him or her then much of that potential can remain untapped.

5. Growth

The coach must never neglect the importance of growth. A continuous honing of skills and setting new goals, learning new tactics etc. is necessary if the player is to continue to progress. Often coaches take players up to a certain ‘plateau’ then the development stops and levels out. Growth must continue throughout the player’s career, at no time should it be allowed to come to a stop. There must always be progression, without this there can only be stagnation.

If you are to aim for the top levels it is critical that there is mental growth too and that you start to analyse your performance and what is happening when you compete and train. This should become a regular part of your development and become a habit. What often distinguishes the elite from the ordinary athlete is the ability to make mental assessments more or less automatically. Any mental programme should be systematic and goal-oriented and it should indeed be on-going and continuous and progressive. This doesn’t mean that you need extra time to train, the mental side should indeed be integrated into and become an integral part of your everyday normal training.

Developing Players: Move with the Times

Rowden 2012

Do we want ‘New players, old styles’, is this the way forward? Even more so do we want ‘New Coaches, old ideas’? Surely if we do not continuously seek new things we will stagnate. Are too many players in these modern times of athletic, dynamic table tennis just too ordinary, too conservative and too predictable? Do they fail to take risks or try new techniques/tactics through fear; are they afraid of losing what they have? And are they influenced by all the players around them to become just one of the herd and to ignore their individual talents?

Without change or innovation and the individual focus, which should be constant and ongoing, we will achieve very little. This should appear to be obvious. Yet unfortunately throughout Europe the coaching methods very rarely mirror this approach! Often the reason appears to be ‘the mindset’ rather than anything else: it’s easier to carry on with the same old programme, use the same old methods and follow in the footsteps of those who have gone before!

Seizing the initiative at the earliest point in the rally is vital in modern table tennis and is a skill which should be encouraged from an early age. But taking the initiative requires both mental effort and technical qualities and these aspects must be fostered in tandem. Equally the individual development is paramount as each player is unique and no two players of even very similar styles will play the same. What is vital is that each player fully comprehends exactly how he/she wins points and where the specific strengths lie. There is no room in modern table tennis for obvious weaknesses; the modern player must have strong all-round skills and be able to cope with all eventualities and styles of play.

To be effective in taking the initiative, players must upgrade their serves to the highest level and continue both to monitor themselves in this area and to research any new developments, which may be applicable in particular to their own style of play. The better the serve, the more opportunity the player will have to attack. The objective of course is through the efficiency of the serve, to be able to attack strongly and gain advantage over the next one or two balls. Once the server attacks the opponent must be kept under constant pressure. This does not necessarily mean that the attack has to be totally relentless. Often change can be equally if not more effective: hard and soft, long and short, spin and drive, angles and placement etc. The ‘stop/start’ game which the Asians use so effectively could be worked on a great deal more in Europe.

In the receive situation the objective is to keep control, while trying to snatch the initiative. This can be done by good short play and doing different things within the first few balls. Even in a fast early exchange the aim has to be to keep a measure of control, while looking for an opening. Too many players play too safe before going on the attack: better to try to keep the opponent off balance, then the opening for the attack will be rather easier. If possible, attack first, put more power and/or spin into the shot first, change direction first. Look to apply pressure to the opponent as soon as possible and while trying to keep enough speed in the rally to prevent the opponent getting in, look for every opportunity to attack or counter. Above all the desire to take the initiative should be fostered in the young, developing player. The ultimate personal performance is when we overpower our opponents by initiating all the changes.

Even in the case of defenders the opponent should be pressured in an aggressive manner: fast chops, slow chops, heavy backspin and float, counter-topspin and counter-drive back from the table and varied blocking and hitting over the table. Control of the rally must be maintained, but the will to attack at the earliest opportunity should always be present. Only those who are mentally strong enough will win the battle to initiate.

Speed is undoubtedly the most crucial factor in any style: speed and suddenness of shot, dynamic impact, speed of movement, speed of thought, speed of adjustment and speed of change. If you think and move faster, your attacks will be stronger. Being aggressive is essentially quickness, spin and change and the essentials are a variety of attacking strokes and constant improvement of the quality of these. A major part too of modern table tennis is improvisation. The game is just so fast that it is not possible to prepare and get into the perfect position for each shot and one often has to improvise in every facet of the game. If there are occasions where the player cannot take an offensive initiative then he/she must control the rally in such a way as to keep the opponent off balance until the chance presents itself to create the next attack. There is no room for sequential instability during the improvisation phase; each stroke however unstable must inter-link with the next.

Modern table tennis is arriving at a level of supreme all-round play. The top world-class athletes (and they are athletes) are faster, stronger both physically and mentally than ever before. They are equally comfortable close or away from the table, in all situations and against all types of opponents. They also have balance, the capability to control the game at speed until they can seize on the right ball to be totally aggressive.

At the top level in world play unpredictability is the norm. Change in all its forms is the heart and spirit of table tennis. Changing at the right time and in the right way strengthens your own style and makes you more formidable. Changing first imposes your game on the opponent. Upgrading defensive and even control shots to attack or counter-attack raises your whole level of play and advances your playing style. To be ultra-positive requires you also to raise your tactical awareness and understanding of the game to new heights.

Our sport of table tennis with all its technical changes is developed within a theoretical foundation. As a result coaches need to take the lead in studying the technical/tactical aspects of the game and evaluating the efficiency of various playing styles. This will provide pathways for the future evolution of the game. Coaches can see that our sport of table tennis consists of a number of elements of which speed, as we have already indicated, is the central core and the prime factor of development. Power and spin are also critical foundations, power to add force and potency to our playing style and spin to give stability and to test the opponent’s control limits. The flight of the ball is crucial too in terms of accuracy and on–the-table consistency: the gyroscopic effect of modern topspin cannot be underestimated. Equally the trajectory of the shot will often highlight weaknesses/strengths in your player’s game. Finally as we have emphasised, change in all its forms, pace, length, spin, placement and angles, is the heart and spirit of table tennis. We impose our tactics fully if we win the battle of the change! Top-level players will invariably be very good in at least three of these aspects.

Coaches should evaluate the impact of these five elements on the style and efficiency of their players, to ensure the highest level of shot quality. Quality strokes will evolve and develop if enough attention is focused by the player and coach on these 5 elements, speed, power, spin, the flight path of the ball and change. Each player will of course have a different and unique blend which will be individual to him/her. Each player must also be aware of what works for him/her and where the strengths lie within this blend of elements!

Power

Power — where does this come from in the modern game?

Rowden Fullen (2006)

Years ago when table tennis was rather slower and the men played from much further back, the forehand was executed in a measured fashion – a push off through the legs, rotation of the body, good input from the shoulder and a fast moving arm and wrist. These principles are unfortunately still taught in many countries in Europe even on advanced coaching courses. The game however has changed dramatically over the last ten and especially over the last four to five years. Our sport of table tennis is now faster than it has ever been and the bigger ball has brought even the men closer to the table than ever before.

Not enough of the coaches running top-level coaching courses are looking at what the top players are actually doing and how they are producing power in an increasingly more pressured environment. For a start there is a big difference and always has been, between the men’s and women’s game, not only in the way they play, but in the methods of producing power. Women have to cope with speed rather than with power or spin – they stand closer, play flatter with less spin and stay square almost all the time. As a result they often use the backhand from the middle both on the 2nd and 3rd ball. Many of the top women who use this tactic (eg. Guo Yue and Boros) have in fact extremely strong forehands.

Almost all the top women spin and drive from a square position and there is no transfer of weight from a back to a front foot. Rather than strong use of the legs there is much more use of rotation, both the centre of gravity (hips) and the upper body. Rather than dropping back to try and play power a number of the top women come forward into the forehand side to take the ball earlier and use its existing speed – Zhang Yining, Michaela Steff, Ai Fukuhara and Georgina Pota are all prime examples.

In the case of the top men many either play square or finish the stroke square so that they are ready for the next ball. In many cases again there is no transfer of weight from a back to a front foot, as the game is just too fast. Players who have a relatively square stance most of the time are Chen Qi, Chuan, Boll, Maze, Heister, Kreanga and Blaszcyk. Players who finish square, either by bringing the right foot through, pulling the left back or moving both at the same time are Samsonov, Schlager, Kong, Oh Sang Eun. Players who didn’t finish square when they were younger but now do, are Waldner, Persson, Wang Liqin. Almost all the top men and women tend to have a wide stance in most cases much wider than shoulder width and many men now adopt the women’s tactic of at times using the backhand from the middle on the 2nd and 3rd ball (Waldner and Schlager do it as do Boll and Wang Liqin).

Over the last five years or so even most of the older top men players have moved in closer to the table and have ‘squared up’ to enable them to cope with the faster play prevalent in the modern game. The new generation of Asian players such as Chuan, Hao Shuai and Liu Guo Zheng automatically adopt a squarer recovery position as do many of the younger European players such as Suss, Crisan, F-Konnerth and Gardos. The game is too fast nowadays to play in any other way. There is just no time to go through the full gamut of preparatory movements to play each shot. More and more, players are having to improvise, to try not just to get the ball back (because at top level this is not enough), but to make a ‘winner’ from a difficult if not impossible position.

Maximum speed or power occurs when we use all the units of the body in sequence, from hips to hand for power, or from hand to hips for speed/precision. This rarely if ever happens in fact (and is more likely to happen in set pieces) as in our sport we have no time and are always improvising. It is therefore essential that we learn the final or last movement in the sequence FIRST. This also means in essence that we should really be approaching our coaching and development of young players from a rather different direction.

The single most important quality in any top table tennis player is the ability to be able to adapt to an ever changing scenario and to be able to do this at speed. Waldner recognises this in his book when he stresses the need to master play against all playing styles and also against penholders and lefthanders. What all coaches must appreciate is that a high adaptive capability doesn’t just happen – it is the result of the right training and from an early age. If players don’t have the correct development in this area, they will too often reach maturity with serious deficiencies in their game, (which in fact often does happen in Europe, especially in the case of the women).

Too much of our coaching is based on archaic training methods and too rarely do many of our top coaches not only look at and understand, but also evaluate what the world’s best players are doing and why. The top performers play in a certain way and use certain tactics quite simply because they bring success. Such aspects are particularly brought home to us in the European arena when our top girls take part on high level training camps in Asia, where they have access not only to coaches highly professional in women’s development, but also to several ex-world champions. The first question almost inevitably to the European girls is this – ‘Why do you try and play like the men, why not play a woman’s game?’

Too often practice doesn’t make perfect instead it makes predictable! Practice of course has to be realistic and has to transfer the technique into the competitive situation as well as improving recall and retention into long-term memory. Too often coaches, even at quite advanced level in our sport, use constant or blocked practices, which are more suitable or valuable for techniques executed in closed situations (archery or shooting for example) rather than a sport like table tennis, where the ability to select an appropriate technique is much more important than the ability to repeat the same one time after time. Random (blend of various techniques) or variable practices (varying the execution of one technique) on the other hand entail mixing a variety of techniques throughout the session, which much more replicates the competitive situation and forces performers to be more actively involved in the learning process.

Good coaching allows players competing in open situations to be versatile, creative and deceptive in the competitive environment. Such players are much more likely to be competent at assessing new and different situations and at selecting the most appropriate responses from their repertoire.

Rigidity

Rowden December 2015

The main reason why many athletes aren’t able to take the final step from being really good, to reaching the absolute heights and becoming great, is a matter of rigidity. Performers become locked into certain technical ways of performing and certain tactics and strategies, which work some or most of the time, but not all of the time. But worst of all athletes become locked into patterns of thinking and perception, which do not permit them to change and adapt.

In a sport such as table tennis where we have an opponent at the other end of the table and a different type almost every time we perform, the ability to change what we do to cope with the new situation, is absolutely crucial. Table tennis is one of the sports where adaptive intelligence will make the difference between success and failure and also where reading the situation incorrectly or using the wrong tactics and strategies can be fatal. For a top player being predictable and playing the same against all opponents at all levels doesn’t happen as this would obviously be a recipe for disaster.

The only real comparison if any in technique between differing levels is that world class players will play harder and faster than you, with more dynamic strokes and often earlier timing. Their shots may even be less perfect than yours, because of the simple fact that due to the increased speed they have to improvise more than you do. But most important of all top players customize and refine their strokes as they progress in their careers as we all will, as we develop and reach higher levels. For example a top player may have considerable sidespin on push, block or even topspin strokes which you wouldn’t encounter at lower levels. In most cases however it is not techniques which differ at the highest levels but how these are used, in other words not the technique itself but how it is applied within the area of performance.

Bear in mind too that it’s never the beauty of the technique that’s important but whether it’s effective and effective for the player using it. Also all your individual tactics and strategies are based on your personal techniques. The concept of individual flair, the idea that players can have different techniques within the underlying principles is one of crucial importance in allowing them to arrive at and to create their own personal style. As you can well see for yourself the underlying principles are extremely simple; BH for example more or less in front of body or slightly to the side, played with forearm and not too far away, but the number of personal variations in the technique can be immense.

At the highest levels technique is so refined to suit the individual player absolutely. But also the perception and the mind are honed to perfection. Often a younger international player will comment after losing to an older player of vast experience and equally often the content of the comment is remarkably similar. That the older player always recognizes immediately when the game changes but with the younger opponent this takes time, often two or three points. Older, more experienced players almost always have the edge when it comes either to changing what needs to be done or in recognizing what has changed and how to cope with this.

In many cases too a younger player competing with a world star will make the comment that they were able to stay with the better, more experienced player almost all of the game, but right at the end the older performer did something different, made a change which swung the game in his/her favour. Not only does the more experienced player have certain tactics and strategies he knows he can rely on totally, but he has been in this situation not once or twice but countless times before and this makes a difference.

Table Tennis Player's Bible

Rowden Sept 2013

Do I want to reach my full potential and be the absolute best I can be? If I do then I have to:

• Know and fully understand exactly how I play best and what works for me

• Be responsible for my own development, I am individual and differ from others: only I can feel what is right for me. If coaches and managers try to force me into boxes of their choosing, I almost certainly will not reach my full potential

• Understand that I must always look to progress and learn new things about my game and myself. If I stop progressing and am satisfied with how I play, then I stagnate. My career is finished

• Be able to cope with all types of players and adapt to different situations. If my training is predictable and does not develop adaptive intelligence, then I should look for training that does

• Know myself and understand that everything I do and think affects how I play. I cannot allow the doubts of others around me, lack of physical fitness, lack of mental belief and strength, or any sort of emotion to get in the way of performing at my highest level. If I want to achieve my maximum and get where I want to be MOST QUICKLY, then I must give 100% all the time in every session and every match. There are no short-cuts, there is no easy way, if I want real success I have to give all to achieve it.

Techniques, Rules and Systems

Rowden September 2020

Science is in a similar position to our sport of table tennis. Its practical limits are becoming apparent; it can tell us how to make things but not how to use them.

Because of uncontrolled science our world starts to be polluted in fundamental ways. Science cannot help us decide what to do with the world or how to live in it!

Equally like other outmoded systems table tennis is losing its way in the modern world. Techniques, ideas, materials and equipment are in flux, are always changing. It is therefore painfully obvious that to adopt the purists approach to our sport is both outdated and counterproductive. Systems and academies lead to dogmas, dogmas create fossils, rigidity and clones. The adoption of purity is as limiting as absolute consistency.

On the other hand the great artists understand intrinsically that there is no way they can succeed in our constantly changing sport by a predictable and rigid approach. They therefore prioritise creativity not consistency, the innovatory not the conventional, the exceptional not the usual and unpredictability over regularity. The great individualist, Jan Ove Waldner has been a prime example of such supreme artistry.

With our modern game of table tennis there are two other crucial aspects, to which every aspiring player must pay the greatest of attention and understand completely.

• Once you are able to execute table tennis strokes to perfection and know them inside-out, you may be of the opinion that there’s nothing more to learn. You couldn’t be more wrong. All your training so far has just brought you only as far as the threshold of the entrance. Rules and systems take us only so far, once they are out of the way, you are free of them and able to move on to a higher dimension.

It is only at this stage that you realise that table tennis is an art form; you indeed have the weapons, but now you must cultivate the awareness and understanding of just how to use these effectively and in the best way for you. We are all individuals and should progress and develop in our own individual way. We have to do what science hasn’t been able to do; now we have created something, we must know what to do with it.

• The second crucial aspect is to do with the science of our sport, which has changed with the introduction of the new plastic ball. As we know there is much less spin, more use of power and players adopting a closer to the table position. However unfortunately most players are not fully aware of all the implications.

For example power with much less spin results in a more predictable ball; less effect on the opponent’s side and easier to return. It also results in more conventional play from mid-distance or deep and less alternatives from these areas with less chance to win points or to deceive opponents.

Closer play over the table, on the other hand, gives more diversity and more opportunities to cause problems for the opposition. You can use more variety of stroke with all the early timed variations and there is more spin on the ball whereas at a distance most spin is lost. Also the slower shot, slow roll and drop shot, is deceptive over the table with the plastic as the ball slows rapidly and does not come through.

It would appear therefore that players who naturally adopt a closer to table position will benefit from the plastic ball and indeed it will be necessary for all exponents of our sport to prioritise and upgrade training in over the table areas.

The LTAD Model

Rowden March 2019

There are according to sports scientists, critical periods in an athlete’s career when the effects of training can be optimised and LTAD focuses on these key moments in order to maximise the individual’s development.

Furthermore the model provides sports organisations and coaches with a framework in order to plan and structure the delivery of training in a manner that ensures it fulfils the specific needs of each athlete.

The concept of LTAD is based largely on the work of Istvan Balyi, according to whom sports can be classified as either early specialisation (Gymnastics, Table Tennis) or late specialisation (Track and Field, Team Sports). Early specialisation sports commonly require a four phase model while late specialisation usually needs six phases. An important point to note about the models is that the stages are not necessarily based on age in that research has shown that chronological age is not a good indicator on which to base athletic development models for athletes between the age of 10 to 16 as between these ages there can be a wide variation in the physical, cognitive and emotional development of the child.

Early Specialisation Model

Phase 1—Training to Train

This phase is appropriate for boys between 11 and 15 and girls aged 9 to 14. The main objective should be the overall development of the athlete’s physical capabilities (focus on aerobic conditioning) and fundamental movement skills. The key points of this phase are:

• Further develop speed and sport-specific skills, develop the aerobic base after the onset of PHV

• Learn correct exercising techniques

• Develop knowledge of how to stretch and when, how to optimise nutrition and hydration, mental preparation, how and when to taper and peak

• Establish pre-competition, competition and post-competition techniques

• The strength training window for boys begins 12 to 18 months after PHV

• Special emphasis is also required for flexibility training due to the sudden growth of bones, tendons, ligaments and muscles

• A 60% training to 40% competition ratio is recommended

Coaching specialists should also assess training prior to this phase and utilise the information gathered to ensure any windows of opportunity which have not previously been optimised are done so here. At this stage we would also normally establish whether the athlete is performance or participation based as this will determine the level of commitment and input from both the athlete and the coach. Conversations about future direction and action plans can then be initiated.

Phase 2 – Training to Compete

This phase is appropriate for boys aged 16 to 18 and girls of 15 to 17. The main objective should be to optimise fitness preparation, sport/event specific skills and performance. The key points of this phase are:

• 50% of available time is devoted to the development of technical and tactical skills and fitness improvement

• 50% of available time is devoted to competition and competition-specific training

• Learn to perform these sport specific skills under a variety of competitive conditions during training

• Special emphasis is placed on optimum preparation by modelling training and competition

• Fitness programs, recovery programs, psychological preparation and technical development are now individually tailored to the athlete’s needs

• Double and multiple periodisation is the optimal framework of preparation

Here the training becomes very specific to the individual athlete and therefore requires good communication between coach and athlete – the coach-athlete relationship has therefore developed into one of mutual respect as trust and rapport has been developed. It is not uncommon to experience transition at this stage as schooling structure can change and so too the social environment as the athlete becomes more independent both in and out of sport. The balance of power and responsibility often shifts at this stage and therefore it is critical that it is managed appropriately.

Phase 3 – Training to Win

This phase is appropriate for boys aged 18+ and girls 17+. The main objective should be to maximise fitness preparation and sport/event specific skills as well as performance. The key points of this stage are:

• All of the athlete’s physical, technical, tactical, mental, personal and lifestyle capacities are now fully established and the focus of training has shifted to the maximisation of performance and peaking for major events.

• Training is characterised by high intensity and relatively high volume with appropriate breaks to prevent over training

• Training to competition ratio in this phase is 25:75, with the competition percentage including competition-specific training activities.

Phase 4 – Retirement and Retainment

The main objective should be to retain athletes in coaching, officiating, sport administration etc.

Overall Notes on LTAD

Many NGB’s have adapted the LTAD model to suit the specific demands of their sport and coaches base their practices around the model. This must be done however in a timely and appropriate manner. The model is one which encourages long term commitment to sport and recognises that athletes will pass through a number of stages in their development. One of the most important factors is the level of emotional intelligence of the athlete.

This is the capacity or ability of the athlete to recognise, interpret and regulate their thoughts and feelings and to therefore cope under pressure. This is a skill which can be developed and managed and thus needs careful consideration as it allows consideration of the athlete’s social, practical and personal evolution rather than focusing just on their chronological age.

At some point in an athlete’s career we see a transition as he/she clearly establishes him/herself as a PERFORMANCE athlete. This is a common and usual part of the athlete’s development, but it’s important to note that this can cause organisational stress and needs careful management.

When working with athletes at a younger age one should not expect coaches to explain the purpose and reasoning behind every aspect of the training. As however the athlete matures and becomes more emotionally intelligent he/she becomes more independent, self-reliant and regulatory and I have always found it useful to have a more two way process, where the thoughts and ideas of the player are aired more fully.

Every athlete is different but windows of opportunity should be carefully addressed for each individual. With increased emotional intelligence comes the need for lifestyle choices, relaxation and focusing, pre-competition, competition and post-competition routines, as well as nutritional and life organisational requirements.

Also all coaches must bear in mind that they will encounter numerous exceptions to the above age categories. Some children may have a chronological age of say 10, a mental/emotional age of 15 and a technical/tactical age of 17, in which case advancement through the various phases will be much quicker.

Ball Through the Air

Rowden Fullen (1970’s)

As we know from previous articles a topspin ball travels in an arc over the net, drops quite sharply before contact with the table and then shoots forward fast and low after the bounce.

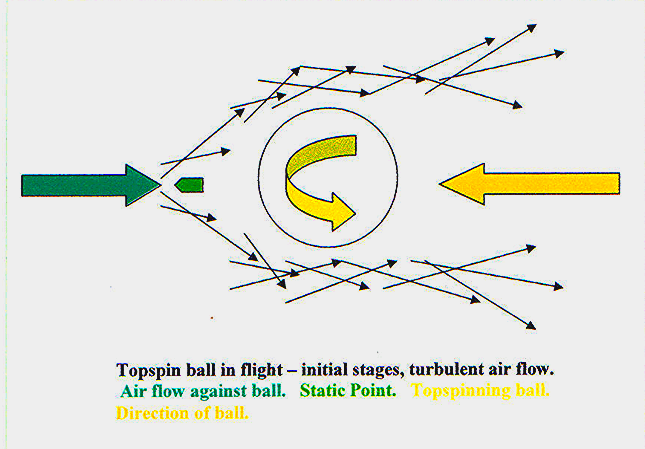

Lets us look however a little more closely at the ball in the air and before the bounce. What we must first understand is that the ball surface is not smooth and contains pockets of air in the surface which react with the flow of air against the ball. We do know that in the case of the top part of a topspinning ball, this spins against the oncoming air while the bottom part is in the same direction. Therefore we have an area of high turbulence at the top and low turbulence at the bottom.

However the air flow round a ball moving at high speed changes from turbulent to laminar as it slows down in the air and this is what causes the ball to dip. Just what do we mean by this?

At the ‘static point’ which is the leading point of the ball at speed there will be an ‘eye’ like at the centre of a hurricane where there is an area of pressure. The flow of air around the ball however will in the initial stages of flight as the ball leaves the racket at speed, be chaotic or ‘turbulent’ in nature. By this we mean there is no smooth pattern of air molecules flowing around the surface of the moving ball.

It is only as the ball slows down that a pattern starts to emerge and the air flow around the ball forms a more ordered outline. We call this a ‘laminar’ effect.

It is of course at this stage that the high and low pressure areas forming on different parts of the ball’s surface have a direct effect and as a result the ball is forced to dip sharply downwards on to the table.

Mechanics of Table Tennis

Rowden Fullen (2004)

SUMMARY

- Introduction

- Trajectory of the Ball

- Absolute Line of Sight

- Smash against Lob

- Flicking the Short Ball

- Counter-hitting

- Service — Speed and Time

- Speed and Spin

- Racket Coverings

- Friction and Bounce

- Bounce on the Table

- Speed, Distance and Time

- Economy of Movement, Key to Speed

- The Radius of the Stroke and Angular Velocity

- The Geometry of the Game

1. INTRODUCTION

Nothing that happens on a table tennis table is inexplicable as long as you are aware of the basic laws of physics. Once the ball has left the racket, the trajectory and direction is determined by the power and spin fed into the stroke. The trajectory itself is determined by gravity, the air resistance and the influence of the spin. A similar stroke will always produce a similar result in terms of spin, speed and direction. One can of course point out that things will not be exactly the same depending on where one finds oneself on the earth’s surface. The weight of the ball can vary by as much as 0.5% depending on whether you play in a position near the poles or in a locality on the equator. However this is really quite meaningless when you consider that the rules allow a variation of up to 5% in the weight and diameter of the ball and at the most 8% when we are talking about bounce.

Far more significant variations occur in air pressure when we talk about height above sea level for example. At 1000 metres air pressure sinks by 12% and at 3000 metres by up to 30%! This has a major impact on both the air resistance and the effect of the spin on the ball in flight. A major championship event played for example in Mexico City will result in the ball ‘flying’ in an unusual manner and the players must be ready for this, as the trajectory of the ball will not conform to expected criteria. When players talk about a ‘hall’ being slow or fast this is a subjective experience. This can depend on different floor coverings, lighting, acoustics, heat and cold or just the size of the room. It doesn’t mean that the ball is moving in an unusual manner.

Questions relating to materials and the differing spins and effects can be rather more complicated as the manufacturing companies have not tried to create standardised tests to measure exactly what their products can do. Often experienced players or testers (or in some cases not so experienced) categorise rubbers in terms of spin, speed and control, but obviously these classifications are purely subjective. Different players will for example use rubbers in differing ways and one player will often be capable of getting far more out of a particular rubber than another player would. Such ‘subjective’ testing can give some useful information but helps little in giving any base for objective measurement when comparing products from different manufacturers. Also materials and indeed techniques and tactics are constantly in change - it is necessary that we always have an open mind and are ready to look at new ideas and ways of doing things.

2. TRAJECTORY OF THE BALL

After leaving the racket regardless of the spin, speed or direction, the ball is influenced simply by 3 factors - gravity, air resistance and spin (Magnus effect)(See diagrams A and B). In the case of topspin, gravity and the influence of the spin work together giving a more arced trajectory (See Diagram C). With backspin gravity and the spin factors work against each other so that the ball will rise initially in a curve before dropping sharply when gravity predominates over the lessening spin (Diagram D). Gravity is always equally strong and always directed downwards. Air resistance is always against the direction of travel and its effect is strongly influenced by the speed of the ball.

With a speed of 8.5 m/second (30.6 k/hour, 19.125 mph.) the air resistance is about equally as strong as gravity. Air resistance however increases or decreases by the square of the speed. This means that a doubling of the speed to 17m/second (61.2 k/hour) signifies a fourfold increase in air resistance. Halving the speed to 4.25 m/second (15.3 k/hour) would bring about a reduction in air resistance to around one quarter of gravity. In the case of fast counter play an average normal speed would be in the region of 12.5 m/second (45.0 k/hour) which means immediately that it’s always the air resistance which is the dominating factor in the early stages of the ball’s trajectory. (In the case of world records for counter-hitting (of so many shots per minute) an average speed of only around 33kph is achieved).

In the case of a top-spinning ball the force of the spin is at right angles to the speed and the rotational axis and as a result strengthens the downward pull of gravity. Very strong topspin is of the same magnitude as gravity and the ball will sink much more quickly. Note that a pure sidespin ball will have a distinct arc when seen from above. In the case of strong backspin the trajectory will veer upwards - here the power of the spin is stronger than gravity.

3. ABSOLUTE LINE OF SIGHT

Of course it is the player’s own skill and technical knowledge which will determine his or her choice of direction, speed and/or spin. There is however an absolute limit for the all out hard smash where in theory one can utilise a completely straight trajectory.

Below the absolute line of sight the speed element in all no spin or backspin balls will be limited as all such balls will require an arc and some margin for error will be needed in the stroke. The no spin smash is the game’s hardest hit (around 31.1 m/second (measured speed off the racket) or 112 k/hour) and gives the opponent the least possible time to make the return. If balls higher than the absolute line of sight are looped instead, this means a slightly safer shot but at a slower tempo. However the difficulty in switching from topspin to smash often means that many players prefer to spin even in this ‘high ball’ situation.

Under the absolute line of sight topspin is used more than any other stroke as the arced trajectory allows more and more power to be fed into the shot while still retaining a high measure of safety with speed. The absolute line of sight is therefore a useful tool in judging the best stroke to play in any given situation.

OVER ABSOLUTE LINE OF SIGHT

- Smash

UNDER ABSOLUTE LINE OF SIGHT

- Topspin, backspin or counter-hitting with well judged (and controlled) speed.

Technique for the low ball

Often in the boy’s game even from an early age it is a good idea to work with topspin as this gives high speed and also a high level of safety. With the help of topspin players can have a comfortable margin for error, a lower trajectory and a lower bounce on the opponent’s side of the table.

Backspin with its straighter trajectory often tends to come through nearer to the end of the table. However in spite of this often the peak of the arc is higher and the ball can easily kick up after the bounce (there is also a reduction of speed at this stage) above the dangerous ‘absolute line of sight’, which leaves the defender open to a flat hit kill. It is therefore important that defenders take the ball as early as possible and above table height. Then they have the opportunity of a low ball over the net and a lower ball after the bounce, as the ‘speed’ element tends to take precedence over the effect of the spin and the ball skids through off the table surface. Also the earlier chop will retain more spin as it is in the air for a lesser time between strokes. Length is also crucial for defenders, either very long or very short, so that opponents have little opportunity to smash.

If defenders can introduce a topspin ball back from the table then this is a highly desirable variation, especially sometimes with sidespin. There will be a big difference between the topspin and backspin strokes and even the best of attackers will make mistakes.

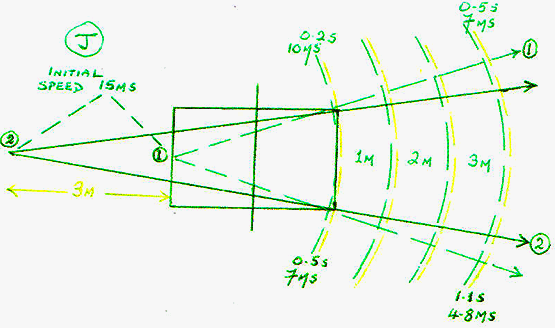

4. SMASH AGAINST LOB

We should also look at the scenario where we face high lobbed balls. Here you will often have the opportunity of smashing from 3 areas, as the ball bounces upwards, at the ‘peak’ position or as it is descending (Diagram E). The ‘peak’ position (2) will need something like an overhead tennis smash and will bounce through high and long giving the opponent time to play the return, although the stroke is relatively safe. Killing the descending ball is also quite safe (3) but as you make contact from further back, you have less of the table to aim at and again the opponent has more time even though the trajectory will be flatter.

Theoretically the preferred contact should be as the ball bounces up (1). Here you have the chance to kill absolutely flat and angle the ball well as you are closer to the net - the opponent has very limited time to react. The problem can be that you have much less time yourself to study the spin and to react to any strange bounce. This contact is therefore a little more unsafe and requires practice (a short arm movement is important in this stroke). An interesting alternative is to use topspin from an early timing position - even though this is a slower stroke which gives the opponent time it results in a more curved shot and a ball which drops quickly after the bounce. Other alternatives are the chop smash or a stop ball taken very early.

5. FLICKING THE SHORT BALL

The flick requires some feeling as the ball must be kept as low as possible over the net and yet it is difficult to create speed from a short ball often served with backspin. Good topspin can create a safer stroke but often it is not easy to achieve this over the table. To reach maximum speed over the table the flick should be taken at the ‘peak’ of bounce on every occasion, though the late-timed stroke played more slowly can also open up possibilities.

It is possible to feed in approximately 10 - 15% more speed into the diagonal flick because of the increased distance involved. (Total available distance 3.1m as opposed to 2.7m)

If you wish to flick more safely, with a higher margin then this will require playing the stroke more slowly. Flicking straight and low over the net will result in a maximum speed of around 8.0m/second (28.8 k/hour) but this would drop to 7.0 m/second (25.2 k/hour) if you wished to have a 2cm cushion over the net. Diagonal play would give the higher figure of about 10.0m/second (36.0 k/hour) dropping by 10% (32.4 k/hour or 9.0 m/sec) if the ‘safer’ diagonal stroke were attempted. The flick can often be angled harder and more easily than the counter hit as it is taken closer to the net and with less speed on the incoming ball. However no amount of training can increase the power of the flick beyond what the natural laws allow. The lifting movement (attacking a ball lower than net height) sets the limit and this can only be overcome by the creation of more topspin. However as we have intimated this is extremely difficult in the case of a low over-the-table ball.

6. COUNTER-HITTING

If you assume that two top players take the ball about 20 - 25cms off the end of the table then in a rally the ball would reach average speeds of around 12 — 14 m/second (43.2 - 50.4 kms per hour, straight and diagonal respectively). In the case of the safe 2.0 cms over the net stroke, speeds would be around 11.0 and 12.5 m/second. When you compare this with the flick, the latter stroke would not achieve speeds in excess of two-thirds of counter play or around 10.0 m/second (36 kms per hour).

The dominance of the Asian players over the years has occurred primarily because they take the ball early, just after the bounce. European players on the other hand take the ball at ‘peak’ or after the top of the bounce. The difference in usable reaction time gives Asian players a real advantage by preventing opponents from coordinating and organizing their best strategies.

7. SERVICE, SPEED AND TIME

The serve can vary a great deal but the service rules and natural laws impose certain limitations. Because the serve must bounce from one half of the table to the other this means a minimum upwards and downwards movement of around 34 - 35 centimetres (17 + 17). The time frame is approximately 0.38 seconds for a backspin or float serve but this can be reduced in the case of strong topspin. One must bear in mind that the limit for a long serve straight is 2.7 metres but this increases to 3.1 on the diagonal.

The time limit from bounce to bounce is around the same for a long and short service. However in the case of the short serve one must add the time from the racket contact to the first bounce which will add 0.15 - 0.2 seconds. The total time for a short serve can be as long as 0.6 seconds compared with the 0.4 for a long fast serve. The speed for a long fast serve will be very similar to the speeds when flicking - between 8.5 m/second (30.6 k/hour) straight, to up to 10.0 m/second (36.0 k/hour) on the diagonal.

8. SPEED AND SPIN

Strong spin presupposes that sufficient power has been used but spin and ball speed are connected and it therefore follows automatically that high speed will more often than not entail high spin.

The short serve will therefore always have a measurable spin which can be reckoned by the number of revolutions per second, while the long serve can have stronger rotation due to the increased power input. We don’t always experience this on the table as we often play with care against the short serve, however even a small lack of touch can lead to a ball in the net or a high return. Aggressive returns such as flick and long push do not require so much touch and are less sensitive to the spin element on the ball, therefore it is safer to play long if you have learned the technique and if the opponent’s playing style allows this. Also flicks against backspin can use the spin already on the ball and will result in a low dipping shot - long, fast service returns over 8.5 m/second will slow due to air resistance and this again helps when using topspin.

With the help of unusual or deceptive actions the server tries to hide the spin, speed or direction so as to gain an advantage over the opponent, lengthening his reaction time or making it harder for him to read the spin. Bear in mind that the variations to be found in the use of spin, speed, length and placement will often be sufficient to cause problems for opponents and it is important that your players can use the same serve in differing ways and execute differing serves with the same or similar actions.

9. RACKETS AND RACKET COVERINGS

After contact with a blade (without rubbers) the ball will retain on return about 85% of the incoming speed. In the case of a racket with 2.0 mm fast reverse rubber the return speed after the contact will only be about 70% of the incoming ball’s pace. For an attacking player the rubber’s task is to preserve the speed as much as possible (a part of the ball’s energy will always be lost against the surface) and at the same time give the player a good chance to create and vary spin during play. It is obviously important that the outer surface of the rubber has high friction, while the sponge can vary in hardness depending on whether the player needs more spin or speed.